As time inevitably propels us into the golden years, a realm where the echoes of Junior Kimbaugh’s lyrics resonate, the challenges and opportunities of senior living demand a profound reevaluation. For architects and designers entrenched in a profession often immune to retirement aspirations, the pressing need to create functional, healthy, and satisfying environments for the elderly becomes paramount.

The Urban Utopias of an Aging Society unfold against the backdrop of global demographic shifts. According to UN projections, the number of individuals aged 60 and above is set to surge by 56% by 2030, doubling to 2.1 billion seniors worldwide by 2050. The weight of this demographic evolution falls disproportionately on ‘greying economies’ such as those in the US and Europe.

In the pursuit of understanding the nuances of this aging paradigm, an exploration into the work of architect and KADK professor Deane Simpson beckons. Simpson, whose interest in the peculiarities of elderly lifestyle communities ignited during a visit to St. Petersburg, Florida, leads us through an architectural journey. His award-winning book, ‘Young-Old: Urban Utopias of an Aging Society,’ underscores a pivotal shift from traditional care-focused models towards those emphasizing entertainment, leisure, and self-segregation on an urban scale.

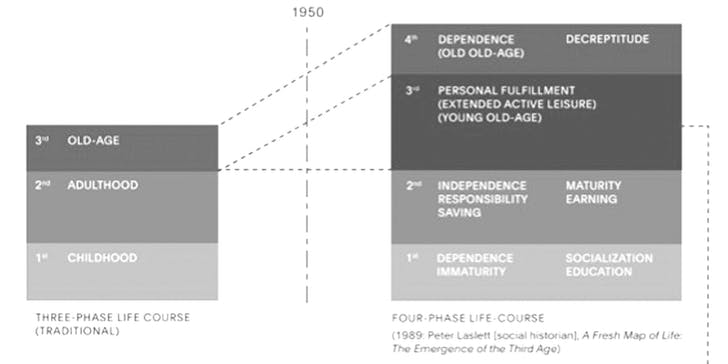

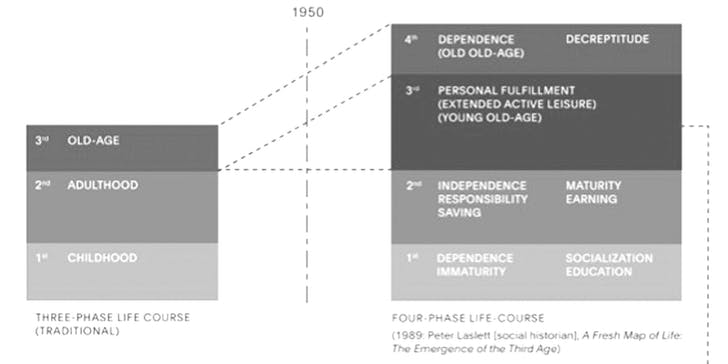

The emergence of the ‘Young-Old’ delineates a distinct phase preceding the ‘Old-Old,’ offering a window of 20-30 years of good health. Historian Peter Laslett contextualizes this phenomenon as a liberation spurred by healthcare advancements, lifestyle improvements, and comparative wealth within the older generation. This shift gained early traction in the US, epitomized by Sun City Arizona in 1954, the world’s first age-segregated retirement community.

The US is recognized to have pioneered early trends in retirement living as it was not tied to the need to rebuild after the Second World War, a task which preoccupied both Europe and Japan. The world’s first documented age-segregated retirement community, Sun City Arizona, built in 1954 and now home to 37,000 seniors, was the first to explore accommodation options for the emerging ‘Young-Old’ demographic. Sun City promised year-long sunshine, leisure-based social activities, companionship and fun—a far cry from the dreaded nursing home.

Today, owner-occupied retirement housing constitutes 17% of the total housing stock in the US. The financial prowess of the ‘baby boomer’ generation has empowered age-specialist developers to vie for prime real estate, reshaping the landscape of senior living. In New Zealand, 12% of those over 75 now inhabit retirement communities, showcasing a global trend diversifying housing typologies for seniors.