From the pages of “Elements of Venice,” a meticulous dissection of the city’s history emerges. The excerpt from the Façade chapter, focusing on Pedestrian Reform, unravels the layers of transformation in Venice’s urban fabric. The 19th-century restructuring, driven by new power structures and public institutions, gave rise to representational buildings that now shape the city’s iconic image.

Millions of tourists strolling from San Marco are unwittingly immersed in a theatrical display of architectural revival. Foscari points out that what appears as ancient Venice is, in fact, a collection of façades designed by 19th-century architects, each contributing to the city’s aesthetic along new circulation axes. The once-representative buildings of banking and commerce have now given way to fashion boutiques, transforming Venice into a global tourism hub.

“Elements of Venice” sheds light on the contemporary phenomenon of icon-hunting tourists. In a world where forms dissolve and images prevail, Venice’s symbols – the Doge’s Palace, St Mark’s bell tower, the Rialto Bridge – have become commoditized icons. Foscari delves into the mindset of tourists who, detached from the city’s history, seek these visual symbols without pondering the impact of tourism on Venice’s authenticity.

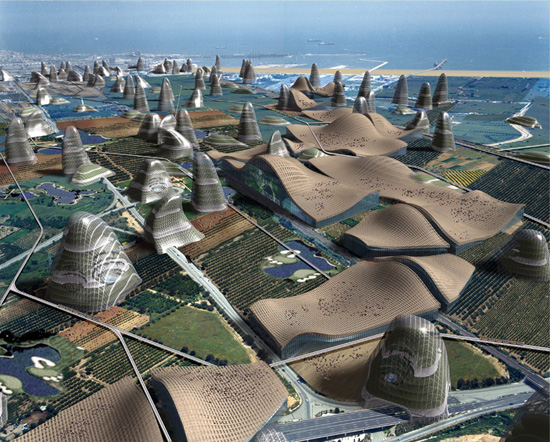

The book reflects on Venice’s reciprocal contamination, where iconic symbols are reproduced on a vast scale, transcending the city’s borders. Enterprising managers, attuned to the allure of entering an imaginary world, replicate Venetian icons in shopping centers and casinos. This commodification becomes a “fantastic mutation of normal reality,” echoing Thomas Mann’s sentiments in “Death in Venice.”

“Venice Unveiled” invites readers to reconsider the city’s façade, urging them to peel back the layers of historical urban design and question the commodification of iconic symbols in our contemporary, image-driven world. Foscari’s work acts as a guide through the intricate maze of Venice, revealing a city where reality and theatrics intertwine in a dance that captivates the global imagination.