“While exploring insights on Cradle To Cradle certification, I stumbled upon an enlightening article penned by William McDonough in Nature. This piece, subsequently reviewed in Scientific American and summarized on his website, resonates with the themes I’ve been delving into in recent posts. It aligns with the concept of mandating all designs to evolve towards being CARBON POSITIVE, as emphasized in my feature post on Advocacy.

Climate change emerges as a consequence of disruptions in the carbon cycle, a manifestation of design flaws attributable to human actions. Anthropogenic greenhouse gases, acting as airborne carbon, find themselves in the wrong place, at the wrong dosage, and persist for the wrong duration. McDonough astutely likens our role in this to turning carbon into a toxin—a peril akin to lead contamination in drinking water. Intriguingly, when appropriately situated, carbon transforms into a valuable resource and tool.

The prevailing global carbon strategy fixates on striving for zero, employing terms like “low carbon,” “zero carbon,” “negative carbon,” and even framing it as a “war on carbon.” However, McDonough advocates for a paradigm shift in the design realm, urging the adoption of values-based language that mirrors a vision of a secure, healthy, and equitable world.

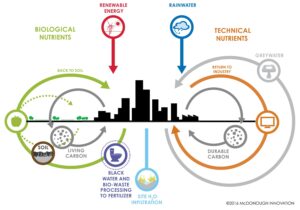

In this novel perspective, crafting urban food systems and fostering closed-loop carbon nutrient cycles can transmute carbon from a peril into an asset. This reimagining envisions the life-sustaining carbon cycle as a blueprint for human designs. The recalibrated language signifies positive intent, prompting actions that contribute more good rather than merely mitigating harm. It introduces a taxonomy classifying carbon into three categories:

- Living Carbon: Organic and integral to biological cycles, fostering fresh produce, robust forests, and fertile soil—a component to be nurtured and expanded.

- Durable Carbon: Resides in stable forms like coal, limestone, or recyclable polymers. Spans reusable fibers, enduring building elements, and infrastructure that can be repurposed over generations.

- Fugitive Carbon: Unwanted and potentially toxic; spans CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels, ‘waste to energy’ plants, methane leaks, deforestation, and various industrial and urban processes.

Working carbon, a subset of these categories, is delineated as material harnessed for human use. Whether it’s working living carbon in agricultural systems, working durable carbon in circular technical processes, or working fugitive carbon derived from fossil fuels for energy—each plays a role.

Table of Contents

ToggleStrategies for Carbon Management and Climate Change

The transformative language also outlines three strategies for carbon management and climate change:

- Carbon Positive: Actions that convert atmospheric carbon into forms enriching soil nutrition or durable structures, coupled with the recycling of carbon into nutrients from organic materials, food waste, compostable polymers, and sewers.

- Carbon Neutral: Activities that either transform or maintain carbon in durable, Earth-bound forms across generations. Renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydropower, which don’t release carbon, also fall into this category.

- Carbon Negative: Actions contributing to pollution of land, water, and the atmosphere with various forms of carbon, such as releasing CO2 and methane or introducing plastics into the oceans.

A Blueprint for Climate Action

McDonough’s narrative sets the stage for climate action by revolutionizing our discourse on carbon. Advocating for widespread adoption of this evolved language, he propels us towards a Carbon Positive design framework. The aspiration is a collective journey toward a world that’s diverse, safe, healthy, and just—a world boasting clean air, soil, water, and energy. An economic, equitable, ecological, and elegantly enjoyable world beckons, underlining the transformative power inherent in redefining our relationship with carbon.”