In the realm of urban planning, shade transcends its mere physical presence—it becomes a civic resource, an emblem of inequality, and an essential component of public health. Sam Bloch’s extensive exploration in PLACES JOURNAL draws attention to the imperative nature of shade in the design of urban spaces, an issue pertinent not just to Los Angeles but equally applicable to cities like Cape Town. Bloch sheds light on the repercussions of historical planning, particularly during the apartheid era, which has rendered the affluent suburbs lush with greenery while casting the impoverished into the shadows of slum tenements and shanty towns.

Within the folds of legislation, bureaucracy, and politics, the seemingly innocuous commodity of shade morphs into a luxury. Is it possible that shade is the missing link in forging environmental, cultural, social, and health-related equities? Can a deliberate focus on shade dismantle the urban deserts mandated by current planning paradigms and usher in a new era of equality?

Bloch’s meticulously researched article unveils the intricate layers of this dilemma. The narrative takes us to the sunlit streets of Los Angeles, where a lack of shade prompts local businesses to take matters into their own hands. From banana trees to makeshift canopies, the quest for shade becomes a communal endeavor, driven by the collective desire for comfort and relief from the relentless heat.

Tony’s Barber Shop, standing as a testament to this struggle for shade, becomes a focal point in the narrative. The barber’s efforts to create a shaded refuge for the community reveal the grassroots nature of the issue. It is not just about aesthetic concerns; it is a matter of basic human comfort and well-being.

However, as the article unravels, it becomes apparent that the provision of shade is not a straightforward task. The placement of bus shelters, a crucial source of shade for commuters, is determined by factors far removed from community needs. Decisions are outsourced to external entities, and the installation of shelters is contingent on advertising revenue rather than a strategic response to local requirements. The convoluted history of shelter installation in Los Angeles, where ad space negotiations dictate shade distribution, underscores the disconnect between urban planning and the genuine needs of the people.

The article spotlights the paradox where, within a two-mile radius of Tony’s Barber Shop, decisions about shade become entangled in a web of complexities. It raises poignant questions about who holds the power to decide where shade is bestowed. The very act of providing shade becomes a challenge, with various obstacles like utility disruptions and ADA violations obstructing its installation. In certain areas, shade is essentially outlawed, perpetuating a stark contrast between sunlit privilege and shaded deprivation.

In essence, the narrative prompts us to rethink our urban landscapes. Can we redefine our approach to shade as more than just a physical element, but as a symbol of equality and well-being? Bloch’s article invites readers to reflect on the intrinsic connection between shade and social justice, urging a paradigm shift in urban planning towards a more equitable distribution of this fundamental resource.

Shade is often understood as a luxury amenity. But as deadly heatwaves become commonplace, we have to see it as a civic resource shared by all.

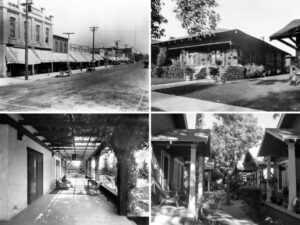

Shade was integral to the urban design of southern California until the advent of cheap electricity in the 1930s.

LOOK AT WHAT HAPPENED TO PERSHING SQUARE, WHERE SUNLIGHT WAS WEAPONIZED TO CLEAR OUT THE ‘DEVIATES AND CRIMINALS.’

“Pershing Square set a template for Los Angeles: the park as an open space to walk through, and as a revenue-generating canvas.”

Adding to the catalog of environmental injustices in our nation is the uneven allocation of shade. Planting substantial trees capable of providing shade is restricted by city regulations, citing concerns about roots damaging sidewalks or disrupting underground utilities. This essentially excludes the possibility of shade in numerous economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. Additionally, the installation of surveillance equipment, such as pole cameras in public parks, contributes to the disappearance of mature canopies surrounding these structures.

A study highlights a significant temperature contrast of approximately 40 degrees Fahrenheit between shaded and unshaded asphalt surfaces. Despite the mayor’s commitment to reducing overall temperatures by three degrees by the year 2050, the implementation of sustainability programs is anticipated to fluctuate across different neighborhoods.