Delving deeper into the origins of architecture and its intricate relationship with landscape, we unravel a narrative that diverges from conventional precepts, taking a closer look at its alignment with Mat-Building—a topic I recently explored in the article titled “Diller Scofidio + Renfro Beat Out Strong Competition at Aberdeen City Garden Project.”

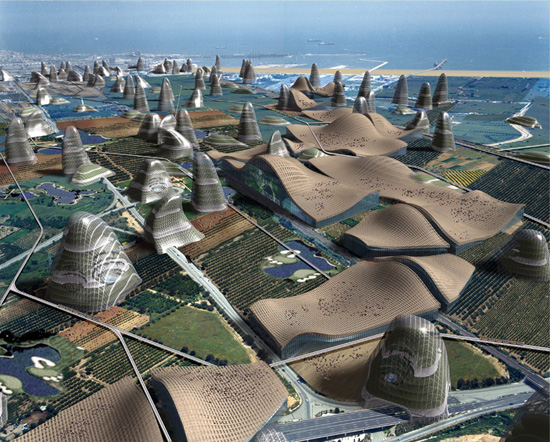

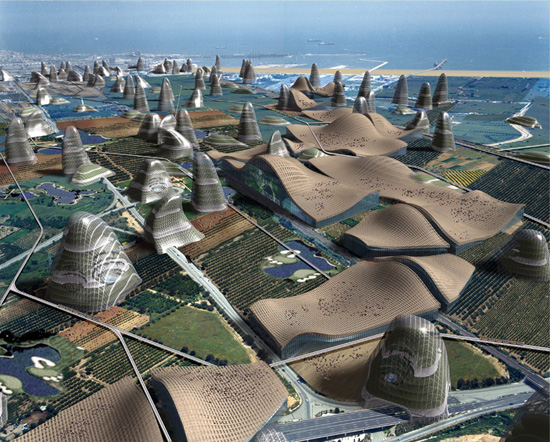

The thickening of the land into a multilevel connected landscape, as discussed, stands in stark contrast to the principles of New Urbanism and other reactionary notions governing city fabric construction. This transformation involves integrating existing fragments, infrastructures, retail clusters, and green spaces into a novel vision of public-to-private spaces, forming a set of nested hierarchies within dense urban contexts—an embodiment of embedded “heterotopias.” This concept draws inspiration from David Graham Shane’s Recombinant Urbanism and Urban Design since 1945, extending its influence to semi-rural “natural” environments, exemplified by visitor centers, experiential museums, and restaurants at historical or “natural wonder” sites—urban in nature despite their apparent rural setting.

In a thought-provoking book review by Ethel Baraona Pohl from Domus, we find an insightful exploration of the evolving relationship between architecture and landscape in the book “Landform Building,” edited by Stan Allen and Marc McQuade in collaboration with Princeton University School of Architecture (Schirmer/Mosel, 2011, 416 pp., US $65).

The book suggests that the nexus between landscape and architecture can be encapsulated by the concept of megastructure, but it also underscores a significant shift over the past decade—from a biological focus to a geological one. The pursuit of responsive architecture has transitioned from biological considerations to referencing landscape, with a contemporary trend looking to the collective behavior of ecological systems as a model for urban spaces. As Stan Allen notes, “Architecture is situated between the biological and the geological—slower than living but faster than the underlying geology.”

This shift in architectural thinking finds its roots in the early 1990s when Landscape Urbanism emerged, emphasizing experiments in folding, surface manipulation, and the creation of artificial terrains. These approaches echo avant-garde projects from the 1960s, such as Hans Hollein’s Aircraft Carrier City in Landscape and Raimund Abraham’s Transplantation I. During this era, architectural proposals inherently included the transformation of landscape, echoing Erwin Rommel’s perspective that “Any work of architecture, before it is an object, is a transformation of the landscape.”

The concept of natural tectonics is proposed as the architectural reconstruction of nature, as articulated by David Gissen. This viewpoint takes a positive stance, encouraging a reconsideration of the idea that architecture can reintegrate nature into the urban experience. Gissen aptly summarizes this perspective by stating, “Through this lens, we understand ‘nature’ as something that was (past tense) in the city. By bringing it back, we reconstruct the former reality of the city but also acknowledge the end of nature as we understand it.”

In essence, this exploration into the intertwined realms of architecture and landscape unveils a dynamic evolution, prompting a reevaluation of conventional notions and paving the way for a more holistic and responsive approach to urban design.